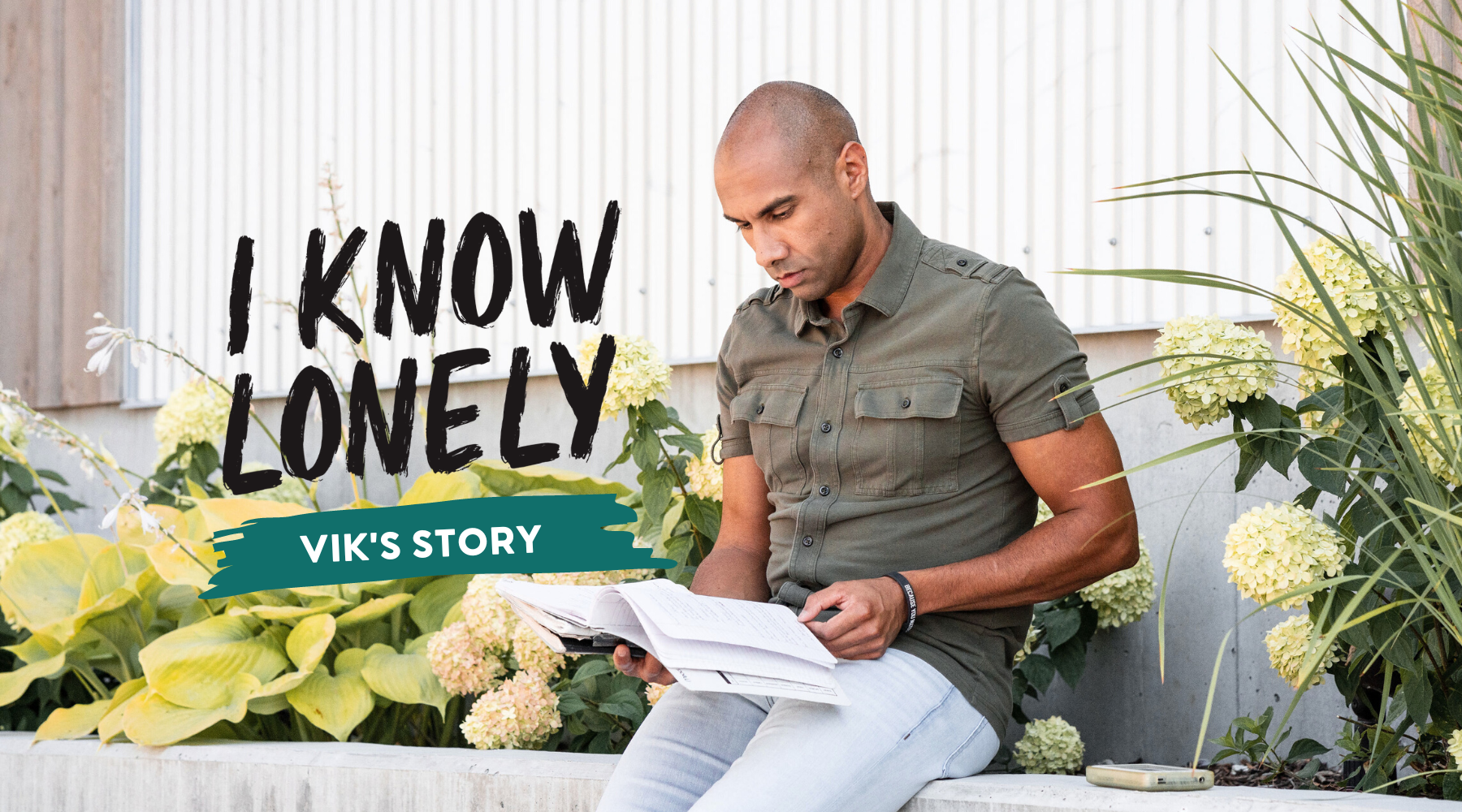

“It’s all small choices. Every day you are presented with a series of choices. You can make the decision one way or the other, but sooner or later, those start stacking up. Those start leading you down a certain path,” Vik Chopra says.

Born in Seattle in 1981, Vik was a good kid and successful student, “pretty much the stereotypical Indian overachiever.” Vik made straight A’s until high school, won the spelling bee in the fourth grade, and was president of his elementary school. In high school, he joined all the extracurriculars, was an honor student, in honor society, the ASB senior class rep, and president of the multicultural club. “I was a natural helper. Like that was very much my thing, just being involved. Involved in school and in academics… everything.”

His parents immigrated from India in the early seventies. “My parents had a really contentious marriage. My father was just very abusive, very verbally abusive, very emotionally abusive to my mom and to all of us kids. They would have at least two to three big blowout fights every year, or my dad would scream and yell.”

“He wouldn’t just fight with my mom. He would fight with the kids too. He would turn against all of us. And then, and then there would be like two to three weeks where he didn’t speak to the whole family. I can remember being very afraid of my father as a child. I walked on eggshells around him. My stomach was always in knots around him. His energy was just very negative and very like a dark cloud that just kind of hung over the house. It was very traumatic. “

Vik’s mom was a neurology nurse. “[She was] very dedicated. Everything I learned about work ethic I learned from her. She was the kindest, most loving mom ever.”

“It was a weird dichotomy where I had like this very, very angry man as my father, but this incredibly loving mother.” Vik’s parents got divorced when he was 24, right after he graduated from college. “My father moved out and I never spoke to him again.”

In junior high, Vik started “having realizations about my sexuality and being gay, although I wasn’t ready to put words to it or understand what was going on. I can remember having those thoughts as a really, really young kid, like six or seven years old, but they really started to come to a head as I was going through puberty. It was very traumatic because I immediately went to a place in my head of ‘This is wrong. There’s no way that I can be like this. Why am I having these thoughts? Why am I like this? This is not right. This something is wrong here.’”

“Growing up in this heteronormative society and Indian culture is very homophobic. I struggled right off the bat. It made me very depressed. I was suicidal. I was pretty much in that dark state, at least a point every day in my life until I finally did come out when I was 24. But being a preteen, I just didn’t know what to do. I kept it a secret.”

“I was in a very, very dark place. When I was 15, I went into a deep, dark depression for about three months. Once I came out of that, that’s when I tried my first cigarette, smoked weed for the first time, and drank for the first time.”

Looking back, Vik attributes this time in his life to the trajectory of the next few years. “That’s where it started because I went from this total goody-two-shoes kid, you know, that was just super about not breaking the rules, following the rules, being the best in school, and then there was like a switch that flipped in my head.”

Vik began to self-medicate at this time. “That’s just the nature of being closeted, right? Of not being able to accept yourself, not being able to love yourself, feeling completely alone, isolated, disconnected, because you feel like you’re the only one in the world that’s feeling like this.”

In college, Vik began experimenting with drugs and different substances. “I got to college and I joined a fraternity at the University of Washington and just kind of went buck-wild with partying, I guess you could say. I went from this guy that was all about school to completely flipping that script.. I pretty much majored in partying in college and school was like a small bit of my actual college experience.”

After his college graduation, Vik got a job at KCTS, the local PBS station in Seattle. “I still probably drank and partied more than the average person. But I still maintained my job; I went to work every day and had a very active social life.”

“When I met my ex, we immediately jumped into taking pills together. Shortly after that, we found a Oxycontin dealer and that’s when everything just started to fall apart.”

“From the surface, it looked like we had a great life. We had a great apartment in a really nice neighborhood in Seattle. We maintained for a while. But the addiction started to rear its ugly head.”

During this time, Vik and his boyfriend started borrowing money from friends and family to pay for their addiction. He got a job at a radio station in Seattle. “They hired me to be their New York sales guy. They were flying me to Manhattan and Brooklyn like once a month. I was taking meetings out there. I was meeting with really cool music venues and I got to meet some cool celebrities, like DJ Rekha.” Vik was in his mid-twenties, “getting to experience the world,” as he says. “It was fantastic, and I got paid to do it. But I just could not keep my stuff together. I was a full blown opioid addict at that point.”

Vik was laid off after nine or ten months. “I totally understand, you know, when you stop showing up for work in big chunks at a time, because you’re just in so much withdrawal and what we would call dopesick – that takes a toll on your life.” Vik went on unemployment and tried to start his own media company, but that didn’t last long. After Vik’s ex lost his job, they ended up getting evicted and finally became homeless in the fall of 2011.

“Have you heard of frogs and boiling water? It’s like that,” he said. “It’s basically like if you put a frog in boiling water, it will immediately jump out. But if you put a frog in cold water and you slowly turn up the temperature and the water gets warmer and warmer and warmer, it will stay in the water. It won’t jump out even until it’s ultimately boiled to death.”

“If we could see the future and could see what our life would become, we would immediately choose something different. We would jump out of the boiling water. But that’s not how life works. Life is a slow boil around us. It’s a slow progression of choices. Slow progression until you ultimately find yourself in this situation that you never in a million years would’ve thought that you would be in, but it’s so normalized because it all happens so slow.”

“All of a sudden you realize, ‘oh my god, I’m now a heroin and meth addict and I’m homeless.’ I go from a college graduate, career in media, boyfriend, a great adult life. Now I’m a drug addict and I have nowhere to live.”

At this point, Vik and his boyfriend moved to Snohomish County, north of Seattle, and found a place to crash with other addicts. “I was giving them like a hundred bucks out of my unemployment just to stay in one of their extra rooms. We stayed there for a couple of months.That’s when we started stealing from stores to make money, because we needed money for food and drugs just to survive. I was getting very little from unemployment and my ex was not getting anything.”

“At that point I was just a total shell of a human being. I did not recognize myself. The way I thought, the way I acted, everything had completely changed.” Vik lost contact with most of his friends and family. “I had burned a lot of bridges leading up to that point, asking for money, borrowing money, not paying it back, you know, like just in full blown addict mode. My number kept changing because I had to get different phones because I couldn’t keep up on bills… I had no connection to my loved ones. I was very isolated. I was very alone, and meeting other people who were in that same state. It just breeds despair and loneliness. That leads to doing acts of desperation, which leads to crime.”

Vik and his boyfriend began stealing and returning stuff for cash or gift cards. “I was just like ‘okay, well, this is what I’m doing now, you know? Because I’ve gotta get high. I gotta get more meth or more heroin or pay for a motel to stay tonight. You’re just in survival mode.” Eventually, Vik and his boyfriend learned how to commit retail fraud and identity theft. “ We did a lot of damage in a year and a half.”

On March 28th, 2013, Vik and his ex were arrested at the hotel they were staying at. “That was the night that my life changed… That’s the day my life got saved because my clean and sober date is March 29th, 2013. That was the last day I ever touched any type of substance.”

Vik pled guilty to 25 counts of identity theft and a drug charge of possession of a controlled substance. “I went from zero to 26 felonies in one fell swoop.”

While Vik was awaiting his sentencing in jail, his mind and body went through detox and withdrawal. “Sitting in jail was awful, but it’s also where I rediscovered myself, because the cloud of addiction slowly dissipated. I found light again in my life.”

Vik was sentenced to 7 years or 84 months in prison; after his sentence was reduced for good behavior, he served 57 months in a Washington State Prison.

“[After my sentencing is] when I left jail and got to go to prison, which was honestly such a relief. I remember stepping off that prison bus for the first time [in 16 months] feeling sunshine on my face. I wanted to cry. Even being shackled, like in an orange jumpsuit, I was still like, ‘wow, this is amazing.’ I remember getting to leave the unit and getting to walk outside for an hour. It was literally the best hour ever.”

“My family and a couple of friends reached out to me, so I started building back up those relationships.” Vik described this reconnection with his friends and family as “everything.” “I couldn’t have done my time if I did not have the support of my family and a few friends. It meant everything to me to be able to call them, hear their voice, and let them know how I was doing, where my state of mind was.”

During his time in prison, Vik “rebuilt himself, mind, body, and soul.” “I learned to lift weights and to work out on the yard, on the weight deck in prison with like these big burly dudes, and I was this like scrawny little brown gay guy. But I still put in the work and fitness is a huge part of my life and it’s part of how I stay sober. I started writing again and redeveloped my passion to want to be a filmmaker.” The choices Vik made in prison set himself up “to hit the ground running when [he] got out.”

In the last five months of his incarceration, Vik was transferred to a work release center in Downtown Seattle. “I got a real job. I worked at an Italian restaurant in Seattle. I was making real money and got to see my family and friends on social outings.” Vik considers himself very lucky. “I had my bachelor’s degree. I had a career prior to all of this. I knew what life could be. I have a ton of support in the community with my family and my friends.”

“The recidivism rate in this country is close to 77%. The system is not set up for you to succeed. It is set up to be a revolving door. That’s a huge part of the work that I do now in my life,” because “reentry is a huge, huge problem.”

“When I was on work release, I met an amazing person. His name is Spencer and he and I just immediately formed a brotherhood and a bond and a friendship because we both realized that we were both very motivated.”

“We were both entrepreneurial minded and we had film projects that we wanted to do. So ultimately, we just had a meeting of the minds one day and were like, ‘let’s just start something together.’ We wanted to tell stories of people getting out of prison, positive stories, stories like hours of people that use their time to better themselves that were trying to break free from these shackles of the system of recidivism of their life prior and to do something amazing with their life.”

Together Vik and Spencer founded “Unincarcerated” to shift the viewpoint on humans with a criminal record. They have several documentary films in production.

“When I heard about Only7Seconds, I was like, ‘wow, that’s really, really impactful.’ And it’s so important because I think about how lonely I felt in my addiction and in my time leading up to my incarceration and in my incarceration. I think about how lonely all the men in prison that I did time with feel. And I think about the lack of connection and it’s just like it’s an epidemic – everybody feels so isolated and alone there.”

Vik’s advice to anybody feeling hopeless, especially those in incarceration: “There’s always hope. There’s always another way you can do this. You can overcome what you’ve been through and you can make a better life for yourself. You can do amazing things. This is not going to define you. This does not have to define you unless you let it define you.

I do not let this brand of being a felon or a criminal define who I am because I am not that person anymore.

Anybody at any point in their life can make a different choice and then make another choice and another choice to make their lives better. It’s not some secret, it’s not reserved for a certain portion of a population. You can literally pull yourself out of any situation; no matter how dark or no matter how disconnected or lonely you are.”

Vik attributes the relationships in his life for his success today.

“Human connection is like oxygen to me.“

“Relationships are probably the most important thing in my life. I would not be where I am without the people that I have in my life that have supported me that never gave up on me, and the new relationships that I’ve developed since getting out.”

“Everybody has things that they might have shame around, but to be able to just be your authentic self with people and to just lay it all out on the table and have people that accept you and love you… that’s the greatest thing in this life. I feel that’s what I’m most lucky to have because I have true, amazing, beautiful connections, and I can always be myself.”

Watch: Vik’s Story on short video | Listen: Vik’s Story on the podcast | Access: Resources

View comments

+ Leave a comment